This is a co-authored post by our Casey Schmitt and Rebecca Keyel, a student in UW-Madison’s department of Design Studies.

This is a continuation of a two-part entry. See Part I for context.

X-Men: Days of Future Past

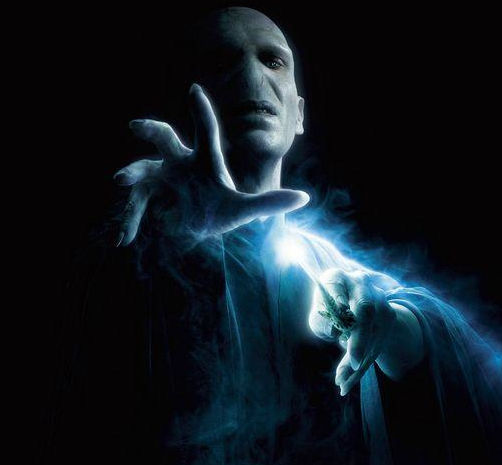

Of the major superhero franchises, perhaps none has been more celebrated as social commentary than X-Men. The X-Men books and films tell the story of genetic “mutants” who are born with fantastic superhuman powers, shunned by greater society on account of their difference. The X-Men, led by the paraplegic telepath Charles Xavier, are “sworn to protect a world that fears and hates them,” often against the militant mutant known as Magneto, who holds ordinary humans at fault for their prejudice.

Since 1963, the X-Men have often been touted as an allegory for civil rights and the internal struggles faced in movements to counter prejudices against ethnic minorities, differently-abled individuals, and, more broadly, anyone who feels “different.” The comic books themselves were especially notable for the team’s diverse roster and celebrated storylines like writer Chris Claremont’s “God Loves, Man Kills” and “Days of Future Past” that focused especially on the universal dangers of xenophobic hatred.

Rhetorician William Earnest is one of many to trace how the X-Men films have stressed a particular attention to the stories as LGBTQ allegory. He cites the scapegoating dialogue of McCarthy-esque antagonists, conversations between characters about “passing” for normal, and a conversion-therapy mutant “cure” storyline that dominates much of the series’ third film. He also highlights a cleverly worded scene in which a mutant character “comes out” to his parents, to their dismay. The 2011 film, X-Men: First Class, includes not-so-subtle dialogue about mutant “pride” and a joking reference to “don’t ask, don’t tell” policies. Beyond the screen, gay activist and actor Ian McKellan, who plays Magneto in the films, has repeatedly said he was drawn to the role by director Bryan Singer’s explanation that “Mutants are like gays. They’re cast out by society for no good reason,” while First Class screenwriter Zack Stentz has also stressed that the allegory is intentional.

With this in mind, audiences are primed to see the films as social commentary and advocacy. The series’ most recent installment, Days of Future Past, however, gives only slight nods to the LGBTQ theme. The plot mirrors the Claremont story, in which one hero travels back in time from a post-apocalyptic future brought on by the assassination of an anti-mutant demagogue to warn the X-Men of the past of the need to overcome differences without murderous violence. In a broad sense, this narrative is still in place. Yet overall there are many other elements in the film that overshadow this theme and, ultimately, there is very little argument or activism to speak of.

Set primarily in the 1970s, the film makes no reference to the very real civil rights campaigns and complications of the era. Beyond this oversight, however, the film really doesn’t forward broader civil rights interests in practice either. DoFP features an overwhelmingly white, male cast, and all are at least implicitly heterosexual. The one lead female role belongs to the shapeshifter Mystique who represents difference well when in her blue-skinned form but who spends much of the movie with conventionally attractive blond hair and blue eyes. Women and ethnic minority characters—crucial to the original Claremont telling of the tale—appear in supporting roles with very little dialogue, and are mostly killed off in the film’s climactic scenes.

The central characters of the film are the archetypical action hero Wolverine and Xavier himself, though Xavier’s handicap is removed for the better part of the story. The central allegory seems no longer to be one of social activism and civil rights, but of a single white man’s struggle with his own lost sense of masculinity and self confidence.

These changes are subtle, but for all the celebration of X-Men as minority allegory, the film is still very much about the concerns and actions of white, straight men. Would it have been difficult to write a script or cast roles that included a greater spectrum of ethnicity, gender, and physical abilities? No—though it might have worried studio executives. That is, for all the talk about social commentary and hidden rhetorics, these films are still designed to make money and to avoid alienating audiences by pushing partisan issues.

Conclusions

So are these films rhetorical? Well, yes, but not nearly as “revolutionary” as they might be. Imagine an X-Men movie with a young female minority traveling back in time instead of a middle-aged white man. Imagine an X-Men movie in which the team is made entirely of women, or one that features gay marriage as its central plot point. The comics have done all of these things. And even they haven’t changed the world but, rather, echoed the public sentiments already at play in American society.

The same might be said of Captain America, who of course sticks up for American ideals by rejecting overreaching government surveillance, but does so by fighting against Nazi infiltration and allying with morally ambiguous super-spies. The social commentary is perhaps palpable, but it’s also fairly elementary and ultimately secondary in purpose.

Superhero movies give audiences a chance to cheer for an idealized protagonist who pushes for a better world. In this way, superhero movies both present a constitutive ideal and contribute to larger social movements with their “hidden” rhetorical elements. Yet, as a recent article on Crave noted, studios like Marvel and Fox “don’t make complex motion pictures full of rich allegories; they make broad, universally relatable fables in which fun characters with superpowers overcome all odds.”

As lifelong comic book readers, we’re glad to see some of our favorite characters being embraced by world audiences and we’re glad to see their stories told in fun and creative ways, but we caution against celebrating Captain America and Wolverine as real champions of social change. The actual heroes are out in the streets, stomping the pavement, and making more regular, explicit challenges to the status quo on a day-to-day basis. Your mild-mannered social activist doesn’t even need a cape.