Last week, Capital New York revealed that Wikipedia edits made to a number of entries on police brutality traced back to 1 Police Plaza, the headquarters of the NYPD. Among the entries edited were those for Eric Garner, Amadou Diallo, and Sean Bell—all unarmed black men killed by police in New York—as well as the entry for the city’s unconstitutional stop-and-frisk program. The two officers involved will face minimal punishment for using NYPD computers for “personal activity.” While some may see this as a lesson on the credibility of Wikipedia, I argue that it’s simply a more blatant illustration of the racial biases that suffuse narratives of police brutality across all media.

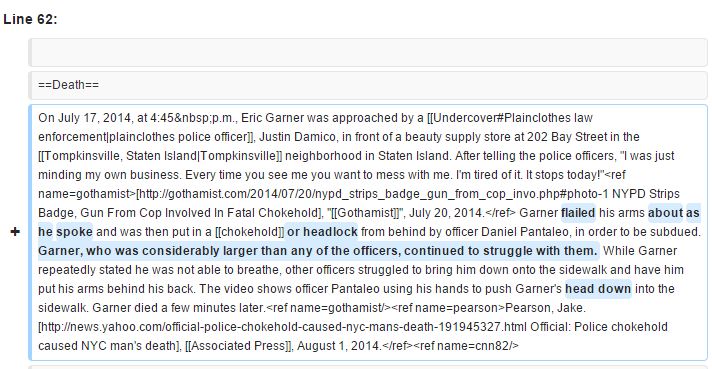

All of the edits were intended to minimize or erase traces of police brutality and misconduct from the entries in question. For instance, in the Eric Garner entry, the phrase “chokehold” was replaced by “headlock” and an extra phrase was added claiming that Garner was “significantly larger” than the officers involved. Elsewhere, an NYPD user suggested the entry on Sean Bell, an unarmed black man killed by NYPD officers, for deletion, writing: “He was in the news for about two months, and now no one except Al Sharpton cares anymore. The police shoot people every day, and times with a lot more than 50 bullets.” There were also other unrelated edits to the entries for the band Chumbawumba, croissant, and Sailor Moon.

As Kate Knibbs on Gizmodo notes, no law was broken in the course of editing these entries—anyone can edit Wikipedia. However, Wikipedia’s code of ethics cautions against conflict of interest editing. As the Wikipedia guideline on conflict of interest states:

When an external relationship undermines, or could reasonably be said to undermine, your role as a Wikipedian, you have a conflict of interest. This is often expressed as: when advancing outside interests is more important to an editor than advancing the aims of Wikipedia, that editor stands in a conflict of interest.

There is little question that the NYPD employees editing Wikipedia were experiencing a conflict of interest when editing entries on police brutality and NYPD conduct. Based on the limited editing history, the officers involved were not active “Wikipedians,” but were rather attempting to “bluewash” the narratives of police brutality on Wikipedia, reframing the narrative of these events in a manner more favorable to the NYPD.

First, as many have noted, the tendency to cast black men as violent thugs, dangerous to police due to their size and aggression, reveals racial biases that lead to a staggeringly high instance of lethal force used against suspects of color. Take for instance Ferguson officer Darren Wilson’s testimony on the shooting of unarmed teen Michael Brown: “When I grabbed him the only way I can describe it is I felt like a 5-year-old holding onto Hulk Hogan.” As Jamelle Brouie writes, “Wilson describes the ‘black brute,’ a stock figure of white supremacist rhetoric in the lynching era of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.” Unfortunately, as the recent spate of police brutality and its attending discourse has revealed, the figure of the “black brute” is still alive and well in the media. In the Eric Garner entry, the altered lines about Garner’s physical stature and his behavior at the time of his arrest (“waving his hands in the air”) all point to this same characterization, which in turn supports the NYPD’s assertion that the violent chokehold that killed Garner was a justified use of force. These edits do nothing to enhance the accuracy of the entry, but rather work to support the NYPD’s narrative. In instances such as these, physical size or a less-than-complacent temperament are seen as violent or dangerous in and of themselves.

Second, the edits show a clear attempt to sanitize the discourse of violence in an attempt to justify the NYPD’s actions and programs. For instance, the erasure of the phrase “chokehold” (the illegal maneuver that killed Eric Garner) in favor of the more neutral phrase “headlock” removes not just a phrase from the narrative, but a central question in the debate about Garner’s death. While the officer involved claimed that the maneuver used was not a chokehold, the medical examiner who ruled Garner’s death a homicide noted that Garner was killed by “compression of neck (chokehold), compression of chest and prone positioning during physical restraint by police.” The removal of the phrase changes the terms of the conversation, and erases a significant debate in the subsequent discourse surrounding Garner’s death. In turn, it takes the focus off of physical trauma and violence wrought by white officers upon bodies of color.

Another notable facet of this controversy is its location: the crowd-sourced encyclopedia Wikipedia. On some level, it may not be surprising that the NYPD edits Wikipedia entries pertaining to their actions—after all, Congress and the UK government employees have been caught in the act before. Indeed, college instructors malign Wikipedia as inaccurate and take points off of student assignments when Wikipedia is cited. While as instructors we may frown upon our students citing a crowdsourced body of knowledge, the fact remains that Wikipedia is a commonly-used source of information, and often a valid source for basic information as long as one is willing to engage in some basic fact-checking.

As danah boyd, a prominent internet researcher, writes, while Wikipedia is not a proper encyclopedia, it can be a very effective resource for students when combined with effective media literacy education. Yet, what is most troubling about the NYPD’s edits is that they demonstrate a much more insidious bias that is omnipresent even in so-called mainstream media—those outlets employing professional journalists and fact-checkers who abide by strict codes of ethics. While the officers’ edits may have been made consciously in order to swing the narratives more favorably towards the NYPD, the fact remains that even mainstream news outlets often cast young men of color as criminals and addicts, police brutality as justified, and protests as needless anger. The NYPD’s Wikipedia edits were merely a more blatant manifestation of the bias and strategic reframing that suffuses discourse about race in the United States.