On the island of Oahu, Hawaii, approximately 4,700 people are experiencing homelessness. More than a third of them are unsheltered. The city of Honolulu, along its deep blue ocean waves and bright, sandy beaches, has one of the nation’s highest homeless populations per capita.

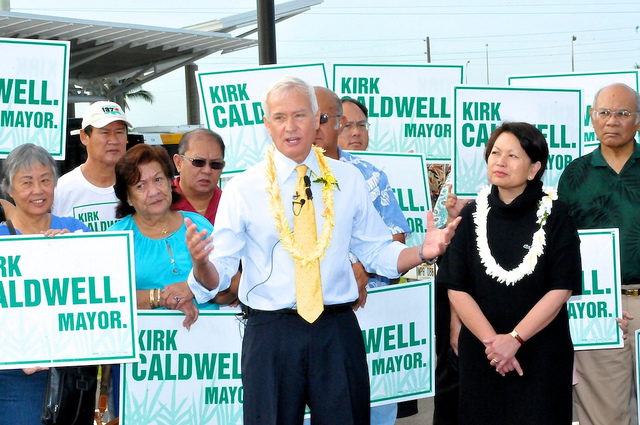

For a community that relies so heavily upon tourism revenues, this doesn’t bode well. People don’t like to vacation alongside homelessness. In the state’s largest newspaper, Honolulu Mayor Kirk Caldwell wrote, “We can’t let the homeless ruin our economy and take over our city” (June 2014). “It’s time,” he said, “to declare a war on homelessness.”

In the intervening months, Caldwell has developed an approach he calls “compassionate disruption” to address this “crisis.” “If we let it be convenient to sleep, for example, on these sidewalks in Waikiki or parks around the island, it just means that those activities continue, and we don’t get people into permanent housing to be treated and made better,” Caldwell said.

This is the “disruption” part of the strategy: Police have stepped up enforcement of laws that already exist that restrict homeless people’s access to public space. They’re giving out tickets and arresting people for sleeping in parks at night and for being “sidewalk nuisances,” and they are seizing people’s unattended personal property. At the same time, Caldwell’s administration has passed new legislation (October 2014) that would make it illegal to sit down/lie down on public property, and that would attach a $1000 fine to public urination/defecation (a frequent problem for homeless people without 24-hour public restroom facilities).

This kind of lawmaking/law enforcement is not unique to Honolulu. Indeed, advocates have documented a trend toward “criminalizing” homelessness in the United States for some time. A similar trend has impacted people trying to alleviate homelessness. Just this week, several people were charged in Florida for serving food to homeless people in a public park.

It’s hard for me to think of these kinds of actions as “compassionate.”

To disrupt is “to break apart, to rupture, to throw into disorder.” The idea behind Caldwell’s strategy appears to be to make it so uncomfortable to be homeless that one would have to be “crazy” to not seek help. What Caldwell seems to be missing is that that’s already true of homelessness. It has never really been terribly convenient to sleep on sidewalks or in parks. It is also not as easy as one might think to find effective help. Homelessness is already often a state of disorder; it is itself a state of disruption. These efforts work to make already undesirable, chaotic conditions even more undesirable.

How, then, might it be “compassionate” to seize people’s personal property and make life on the streets even harder? How does Caldwell frame disruption as a positive strategy?

First, Caldwell’s rhetoric surrounding his “compassionate disruption” policies frame homeless people as pitiable, and in need of guidance. “I think it is incredibly cruel to just drive by homeless folks and ignore them as if they don’t exist – those who have mental challenges and addictions – and say let them fend for themselves,” Caldwell said.

Here, he reduces a highly diverse homeless population to people with “mental challenges and addictions,” calling into question their decision-making abilities. The problem, Caldwell continually implies, is not that there aren’t enough services (there aren’t), but that people aren’t choosing to use them. It is compassionate to help people get the services they need. It is compassionate to force people to do “what’s best for them.”

Secondly, the rhetoric of “compassionate disruption” portrays housed people who “help” homeless people as good citizens. It is what “civilized people do and it is what Americans do.” This, of course, implies that Caldwell’s policies are “help,” and that one should feel both civilized and patriotic for supporting these policies. As “compassionate disruption” makes the audience feel pity for homeless people, it makes them feel good about not “just driv[ing] by homeless folks.” Conversely, people who don’t support these policies (i.e., advocates working for alternatives), and homeless people themselves, are represented as less “American,” less civilized.

Third, Caldwell’s repeated turn to “compassionate disruption” is paired with policies that appear to reward homeless people for seeking help. Honolulu has begun to allocate millions of dollars to a Housing First plan that aims to house a fraction of the city’s homeless population (estimates vary). It certainly appears compassionate to provide housing to homeless people, especially housing with “no strings attached,” as the Housing First model demands.

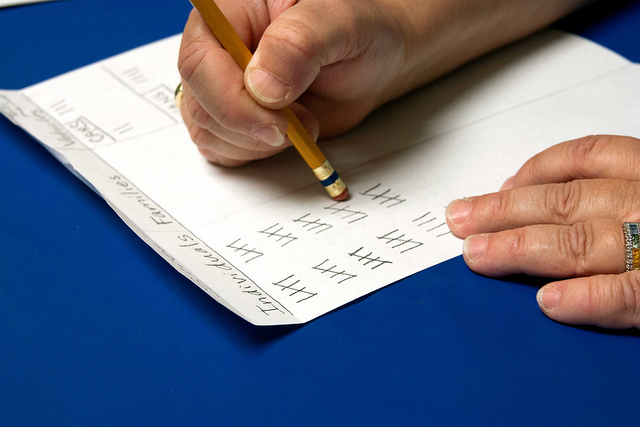

But these apparent rewards work to mask other troubling policies. The number of tickets issued on behalf of “compassionate disruption” in just the first six months of 2014 is more than three times the largest estimate of Housing First apartments projected to be created in Honolulu over the next several years. Caldwell is also currently considering a plan to “relocate” a portion of the city’s homeless population to a camp on Sand Island, the site of a former Japanese internment camp, and former home to ash and solid waste dumps as part of his strategy.

The rhetoric of “compassionate disruption” serves as a reminder that rhetoric has very real material consequences. How we talk about homelessness, and about helping, influences the policies we establish to address these issues and the ways we respond to people living in states of disruption. Caldwell’s policies have been gaining steam in the public and in the legislature, even as advocates resist. As they do so, they help to define what “compassion” looks like on Oahu, and maybe even beyond.