This post was co-authored by Ashley Hinck and Judy Y.

During January 2014, China and Japan continued their recent criticisms of each other’s regional policies. But this time, they took a different approach: Harry Potter metaphors.

Liu Xiaoming, Chinese ambassador to the UK, published a January 1, 2014 op-ed in The Telegraph, criticizing Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s recent visit to the Yasukuni Shrine, which enshrines 14 WWII Class A war criminals. Liu wrote,

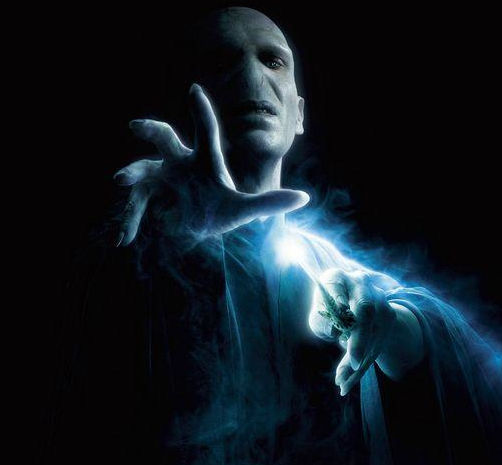

“In the Harry Potter story, the dark wizard Voldemort dies hard because the seven horcruxes, which contain parts of his soul, have been destroyed. If militarism is like the haunting Voldemort of Japan, the Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo is a kind of horcrux, representing the darkest parts of that nation’s soul.”

Liu calls Japan’s actions a “serious threat to global peace” and calls the international community to “high alert.”

Keiichi Hayashi, Japanese ambassador to the UK, responded with another op-ed in The Telegraph. He says,

“East Asia is now at a crossroads. There are two paths open to China. One is to seek dialogue, and abide by the rule of law. The other is to play the role of Voldemort in the region by letting loose the evil of an arms race and escalation of tensions, although Japan will not escalate the situation from its side.”

Hayashi ends by calling for dialogue between China and Japan.

While it may seem funny to hear Harry Potter references in serious, carefully planned diplomatic discourse instead of conversations among 12-year olds, China and Japan’s references to Voldemort are in fact quite serious and strategic.

First, Harry Potter references work to gain the attention of a Western audience. For them, the Harry Potter metaphor is familiar, even if the detailed regional history of Asia is not. By calling Japan Voldemort, and the Yasukuni Shrine a horcrux, China offers a simplified version of the bitter history between two nations. Since the territory dispute could be traced back to the mid-nineteenth century and the history textbooks in either nation fail to reflect the entire truth, a reference to the world’s most popular fantasy novel saves a tedious record of time and events and easily appeals to Western audience.

Liu’s op-ed virtually repeats the major arguments in China’s previous diplomatic discourse. The Voldemort metaphor, however, marks a new rhetorical style in contrast to the conventional dry and dogmatic statement. This strategy not only justifies China’s claim to the sovereignty of the Senkaku Islands by reminding the world of Japan’s brutal invasion in WWII, but also argues that Japan’s intent is to take over the world. Voldemort’s goal throughout the Harry Potter novels was to gain complete control over the wizarding world through any means necessary. Each time Voldemort was killed, a horcrux would allow him to begin his evil plan again. China argues that Japan’s militarism is just on the horizon. Calling the Yasukuni Shrine a horcrux indicates that Japan has not fully repented her sins in the past and the enshrining of convicted war criminals would re-open the door for Japan’s militaristic actions.

Japan also picked up the Voldemort metaphor to develop her own version of Sino-Japanese relations. In response, Japan refutes China’s claim that Japan is Voldemort and instead argues that China is actually adopting Voldemort’s evil goals. Hayashi seeks to redefine Voldemort’s most important characteristics, shifting from the presence of horcruxes, to an escalation of conflict at the expense of dialogue and democracy. Hayashi asserts that militarism is a ghost, not a horcrux: it might be haunting, but it cannot come back to life.

Second, China and Japan’s Voldemort references serve to identify the other as “evil.” In China and Japan’s references to Voldemort, they adopt a level of discourse that assumes that the other is completely evil, with no reason to trust the other side. Consequently, the disagreement over the Yasukumi Shrine or the Senkaku Islands becomes a question answerable only through dichotomies: evil vs. good, right vs. wrong. A discourse reduced to questions of evil vs. good leaves no room for dialogue, compromise, and negotiation. Adopting such dichotomous language demonstrates the increasing tension between China and Japan.

While such vitriolic language may be typical in domestic media and political commentary in each country, such accusations are not often seen in diplomatic discourse. On the other hand, a polarized description of the world and constructing an evil other as the enemy are common strategies in war rhetoric. Targeting an international rather than a domestic audience while using this type of rhetoric indicates that both China and Japan urge their audiences to take sides.

The stakes in the dispute are high for both Japan and China. Both nations are seeking to break the restrictions caused by post-war geopolitical structures. Japan attempts to revise the Peace Constitution and achieve normalization of the army. China hopes to break the First Island Chain to acquire more freedom along its coastline. For Japan, the normalization of the army is like a closure of the past, while China seeks the start of a new future. Calling the other side evil justifies each country’s geopolitical goals.

At a time when both Japan and China are looking to gain support from the international community, convincing Western audiences may be an important goal. Ultimately, the question becomes, why aim to reach Western audiences by using evil vs. good language? We believe there are at least two reasons for this choice. First, they might have learned it from the West. If George W. Bush could successfully wage the war against terrorism through an “us vs. them” argument, why can’t an East nation use a similar strategy? Second, historically, both China and Japan have been portrayed as a threatening evil power to the Western audience, and especially American audience. Invoking the public memory of a Pearl Harbor Japan or a Communist China would push the United States to take a side in the dispute. Whichever reason, it is clear that Western audiences may be hearing more from China and Japan in the coming months. Who knows—we may be hearing about metaphors from The Hunger Games next.

Pingback: FANDOM SPOTLIGHT: Fan Based Activism Research Project | The Geekiary