Even as a qualitative scholar, I frequently work with statistics. I do not gather many numbers myself, but I rely heavily on the data collection efforts of others. Because I am most often writing about homelessness, I regularly consult documents like the Annual Homelessness Assessment Report to Congress or the State of Homelessness in America Reports to help describe the scope of the issue.

Earlier this month, for the first time, I participated in the process through which these statistics are compiled – the national Homeless Point-In-Time (PIT) Count. This count is conducted annually* and functions as a one night census for homeless people. My participation led me to some valuable reflection on some of the ethical questions associated with the gathering of this kind of data.

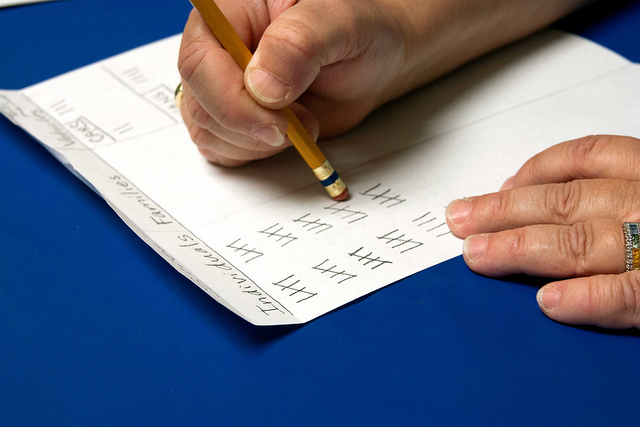

Teams of volunteers are dispatched across our nation’s cities on count night to determine how many people are sleeping in emergency shelters and how many are sleeping in places considered unfit for human habitation. Demographic information is also gathered as part of the count, and all of this information is sent from local communities to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

On the night of this year’s count, perhaps serendipitously, I attended a seminar in which we discussed the relationship of rhetoric to communication ethics. Much of this discussion revolved around Emmanuel Levinas’s concept of the “trace,” the distance we cannot ever fully bridge between people in a communicative encounter. Spoma Jovanovic and Roy V. Wood describe the trace as a place where we “feel the indescribable depth of the difference between the self and the other.” Seyla Benhabib has similarly described the encounter as facing “the ‘otherness of the other’ . . . to face their ‘alterity,’ their irreducible distinctness and difference from the self.”

It is in the trace, in how we choose to address the difference of others from our selves, that an ethics of communication is established. To believe that we can ever fully know another person, or to believe that we can fully know what is best for that person, opens up possibilities for all kinds of communicative violence (e.g., verbal abuse, invasions of privacy, control, silencing). Compassion and kindness and understanding emerge when we acknowledge the unreachable, the unknowable, in the people we encounter.

Every time I encounter someone other than myself, I face the trace. This is true as I speak, as I write, and as I am silent.

With my head full of these ideas, that night I trekked through snow banks, looking under bridges, in tunnels, in parking lots, in wide open spaces, and in abandoned buildings for people who do not have homes of their own. As I walked, I wondered: What does an ethical encounter with a homeless person look like in the middle of the night? How could I acknowledge the trace, to respect the distance between us, even as I invade the space he/she/they had turned into a place of rest and respite?

When a PIT team encounters homeless people on count night, we are under instructions to awaken them. We must then conduct a brief interview, asking for demographic information like age, race, gender, etc. Some of the questions are quite intrusive, asking about sexual orientation, histories of mental illness, military service, and more. We enter people’s resting spaces, we wake them up, and we ask them personal questions in the middle of the night. For reasons I hope are obvious, this can feel threatening (and frightening) to the people the teams encounter.

The statistics we gathered on count night are essential for so many reasons. Federal funding decisions are tied to these numbers, as are policy proposals and decisions at all levels of government. The count also helps establish how widespread is the problem of homelessness. In fact, in the 1980s, homeless advocates fought to establish a homeless count because, they argued, no one would believe it was an issue of national concern without one. Journalists, politicians, advocates, scholars, and homeless people alike depend on the information gleaned from the PIT Count process.

I engaged in this process as an advocate and a scholar, as a person who cares deeply about the power these numbers have and about the circumstances of the individual people these numbers represent. My team did not, this night, encounter any people sleeping outside in our assigned geographic area. I’m grateful for this, because it meant people had found shelter from the -15 degree cold of that night. It also meant that I didn’t have to resolve the ethical questions that were swirling around in my head. I did not have an encounter in which I was asked to ignore or disrespect the unknowable distance between me and the people experiencing homelessness in my city that night.

As usual, I still have more questions than answers. I maintain that the PIT Count is critically important and I wonder how it might be changed to prevent the intrusion of volunteers into the space and lives of people sleeping outdoors. I believe advocates need to continue to have conversations about how to respect the trace amidst these institutionalized processes. In the academy, I believe we must recognize the trace even in the statistics we use to represent collective “others.” And as responsible communicators, I believe we need to understand not just what our numbers represent, but the means by which they are gathered.

* HUD requires the count every other year for communities receiving federal funding to address homelessness. Many communities, like mine, conduct the counts every year.