“Push button. Get Mortgage.” That’s the tagline of Quicken Loans’ new product, Rocket Mortgage. The company introduced Rocket Mortgage to the massive television audience watching Super Bowl 50 in a one-minute commercial. The ad describes a simple push button app that allows people to get mortgages on their phones, which would lead to a “tidal wave of ownership [that] floods the country with new homeowners who now must own other things.”

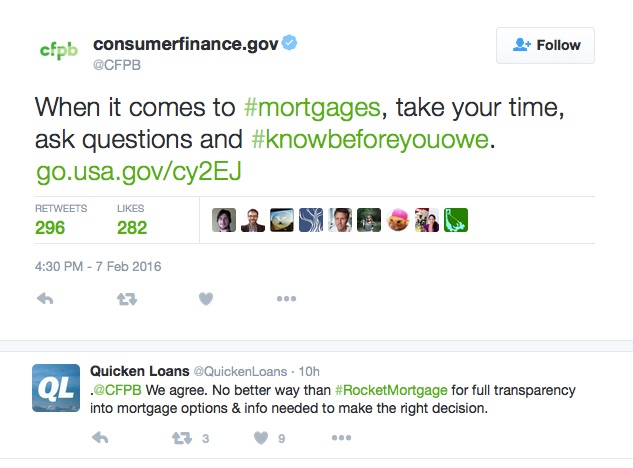

After it aired, there was an eruption of criticism for the piece, titled “What We Were Thinking.” Here is a sampling of the next day’s headlines: Rocket Mortgage Super Bowl Ad Criticized for Encouraging Another Housing Crisis, Is that Quicken Loans Super Bowl Ad an Omen of Another Housing Crash?, Quicken’s Rocket Mortgage Super Bowl Ad Sparks Backlash, and Everything That’s Wrong With the Super Bowl’s Worst Ad. Tweeters, bloggers, journalists, and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau noted the parallels of the promise of quick mortgages to the flurry of irresponsible mortgage-selling activity that caused the 2008 housing and financial crisis. Meanwhile, Quicken defended its product as one that ensures “full transparency.”

The advertisement for Rocket Mortgage is visually compelling and calls upon tried and true cultural tropes. Why then, was it not persuasive? Let’s take a closer look:

“What We Were Thinking” has a strong, consistent cadence throughout. The guitar in the background music is a driving beat. Even when other sounds are laid on top, the underlying sound remains the same – and it’s one that creates a feeling of both urgency and forward motion.

The ad’s narrator does the same thing with her words. She strings together a chain of questions, each beginning with the word “and.” Each question appears to follow from the previous, and together they build a progress narrative:

And if it could be that easy, wouldn’t more people buy homes? And wouldn’t those buyers need to fill their homes with lamps and blenders and sectional couches with hand-lathed wooden legs? And wouldn’t that mean all sorts of wooden leg making opportunities for wooden leg makers? And wouldn’t those new leg makers own phones from which they could quickly and easily secure mortgages of their own, further stoking demand for necessary household goods as our tidal wave of ownership floods the country with new homeowners who now must own other things. And isn’t that the power of America itself?

It’s possible for someone to argue with the premises of any of these questions or with the conclusions they imply, but the narrator does not pause between them to allow this. Instead, her cadence paired with the linked questions fosters a sense of inevitability.

It could seem strange to end this series with “And isn’t that the power of America itself?,” but the progress narrative is so key to the American mythos, and so reliant on notions of inevitability, that it makes sense here. In response to criticism of the ad, Quicken’s chief marketing officer said, “I think that everyone is realizing it’s time for the housing industry to advance.” Quicken Loans is not just selling houses, it’s selling a very particular understanding of progress, one rooted in consumption, accumulation, ownership. Indeed, the American Dream, our leading progress narrative in the U.S., is often defined first in terms of ownership, via “a house with a white picket fence.”

All of this is accompanied by a sense of “no big deal.” The ad’s narrator begins with, “Here’s what we were thinking,” and ends with, “anyway, that’s what we were thinking.” It feels nonchalant, makes it sound like the narrative is just common sense. The mundanity of the activities depicted in the commercial contribute to this feeling: people at a movie, people doing their jobs, people at an exercise class, a woman carrying her baby in the kitchen. These are everyday activities for everyday folks. They are common. In the Quicken ad, progress is common sense. Ownership is common sense.

Given these well worn tropes, one would expect the viewing public to be on board with Rocket Mortgages. But here’s the thing: the message doesn’t match the audience’s experience.

Early in the commercial, as the app promises to “turn an intimidating process into an easy one,” a magician appears on the screen with fireworks and a woman sawed in half. This visual misstep serves as a reminder that what appears to be easy, what is advertised as common sense, is often an illusion. There is not a single scene in which people look at each other during the ad, apart from the one containing the magician, who looks directly at the viewer. It is as though he is trying to hypnotize the audience into buying what Quicken is selling.

In all of the other scenes, people only look at their phones. The household goods that mark progress throughout the piece spin around in the air, but people do not interact with them. This tells us a lot about how Quicken sees its audience – as consumers, but not as community.

The trouble for Quicken is that most of the Super Bowl viewers watched their communities crumble over the course of the 2008 housing crisis, and beyond. They watched as banks were bailed out while their friends, family members, or even themselves, were left jobless, houseless. History is wont to repeat itself, but the backlash to “What We Were Thinking” shows us our collective memories last at least eight years. It may also suggest that “the people” and the banking industry may have now very different ideas about what it means to progress.