This guest post was authored by Matthew Meier, a Ph.D. candidate in Media and Communication Studies at Bowling Green State University.

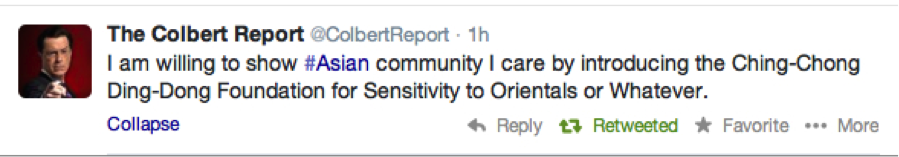

I have a sneaking suspicion that on Friday March 28, 2014, Comedy Central fired an intern. The day immediately prior, the following message was posted to twitter by the Comedy Central operated @ColbertReport twitter handle:

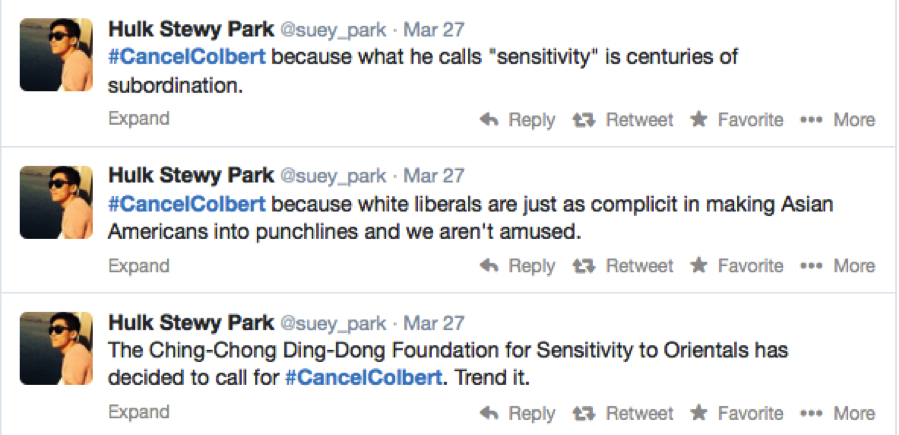

The tweet, which references the March 26 episode of The Colbert Report in which Colbert satirically criticizes Washington Redskins owner Dan Snyder for his dismissal of cries to rename the team something a little less racist, drew the ire of Asian American social media activist and freelance writer Suey Park. In response to the @ColbertReport tweet, Park used her considerable network to get a new hashtag trending: #CancelColbert.

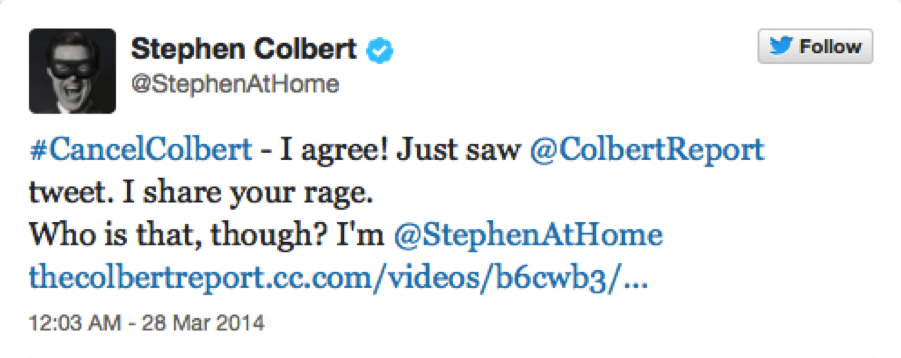

Her efforts created an avalanche of criticism of the show, its host, and its audience. Amidst the cries of racism and white-liberal privilege, even Colbert decided to chime in from his personal handle.

As Colbert’s own admission suggests, the initial tweet from @ColbertReport was decidedly racist and, therefore, Park’s outrage is warranted. What is interesting about this twitter storm (twitternado?) against The Report is that it started, I think, not because the tweet uses racial stereotypes, but because it does not clearly identify a target and, quite frankly, it isn’t funny. Colbert’s character regularly makes bombastic, outrageous jokes that are intended to be understood ironically—that is, as the opposite of what they appear to be—and satirically critical. When those jokes get laughs and make their targets clear, they are powerful tools for social and cultural criticism. When they fail on either account, they can be equally powerful in reinforcing the stereotypes of the status quo.

In this case, the tweet fails in both respects. This is partially the result of attempting to convert a complicated parodic performance into 140 characters, but that explanation seems overly simplistic. A careful examination of the bit from which the tweet was extracted offers more nuance and, arguably, indicated that the tweet was doomed from the start. The bit presents a satirical critique by analogy wherein Colbert’s character attempts to play the foil to Dan Snyder by sending up his half-hearted attempts to atone for the racism he perpetuates by refusing to even consider changing his football team’s logo. In context, it’s reasonably clear that Colbert’s aim is to underscore the racist absurdity of Snyder’s actions by offering “Ching-Chong Ding-Dong” as an equally absurd parodic analogy to the Redskins mascot that Snyder so ardently defends. Thus, the bit swings on Colbert’s attempt to equate his “Ching-Chong Ding-Dong Foundation” to Snyder’s “Washington Redskins Original Americans Foundation,” highlighting the latent racism in the football magnate’s charity by comparing it to an overtly racist, though perhaps in some ways silly, parody. What’s more, because Colbert always performs under a veil of irony, his critique of Snyder’s organization also stands as a critique of his own. That is, by ironically advocating for the use of Asian stereotypes instead of Native American stereotypes, his comparison reveals the ways in which each should be troubling for his audience.

In referencing the bit in context, it is clear(ish) that the joke’s intended target was Dan Snyder. The tweet, divorced from its larger context, implies no such connection to Snyder and therefore any audience unfamiliar with the original context is left to attempt to identify a target from the text of tweet itself in order to make sense of the joke. Arguably, the blue highlighted text of the “#Asian community” hyperlink offers the strongest indication of the tweeted joke’s target. In this way, reducing the satire to a tweet shifts the target from a wealthy, white racist to a marginalized community and drastically alters its critical potential. As many a satirist and scholar suggest, laughter directed at the powerful can be subversive, but laughter directed at the powerless tends to be oppressive.[1] Twitterizing Colbert’s extended bit into a one-liner transforms the joke’s critique of white privilege into an actual example of the racism that such privilege perpetuates in action.

The misrepresentation of the joke’s target, however, tells only half of the story. Even before it was presented in twitter-friendly format, the joke wasn’t funny. The bit contains a few satirical gems such as a doctored image of Native Americans wearing Washington Redskins coats donated by the charity and a jab at Snyder for only providing a portion of funds to purchase equipment because paying the full amount would require selling “a beer and a soft pretzel.” However, the bit also relies heavily on stereotypical caricatures to generate much of the laughter. This latter strategy not only directs the audience’s laughter at the wrong target, but it also overshadows the satirical critique because it earns a much bigger laugh. In fact, by the time Colbert actually delivers the soon to be infamous joke, his studio audience’s laughter has been replaced by bursts of applause. This response, known to comics as “clapture,” suggests that the audience “gets” the joke, but that it isn’t that funny. In this way, even in a larger context the joke doesn’t work because the laugh happens before the stereotypical caricature is revealed to be satirical critique. Given that the joke didn’t actually work in context, its out of context failure is unsurprising.

In sum, Colbert’s twitter debacle reveals two key requirements of rhetorically successful satire—a powerful target and well timed laughter. When satire lacks either of these qualities, as the tweet most certainly did, it turns its subversive potential into oppressive reinforcement of the status quo. Park’s cry to #CancelColbert is an important reminder that when satire fails, it hurts and, from a rhetorical standpoint, that the things that we laugh about are just as important as the things that we talk about.