This is a continuation of last week’s post.

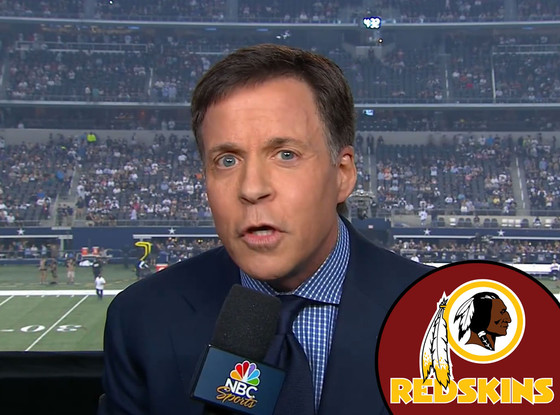

In his prepared remarks, Costas begins by clearing the air of potential accusations and affirming what Redskins fans themselves have stated time and again: that there is “no reason to believe” that Snyder, Redskins players, or their fans harbor any “animus toward Native Americans or [wish] to disrespect them.” He also acknowledges that, despite the Cowboys vs. Indians overtone to the evening’s game, the Redskins name controversy is not simply a matter of race, as “even a majority of Native Americans” are not offended by the name. These opening remarks seek to acknowledge that the people defending the name “Redskins” are not wrong before attempting to demonstrate that the name itself is.

Then, Costas presents his case. He explains that “there’s still a distinction to be made” and proceeds to present a list of other sport teams with Native American nicknames and mascots as a grounds for comparison—a kind of litmus test for when Native American-inspired team names are respectful (or, at least, innocuous) and when they occasionally cross the line. In his first tier he includes “names like ‘Braves,’ ‘Chiefs,’ ‘Warriors,’ and the like” as nicknames that “honor, rather than demean,” asserting they are “pretty much the same as ‘Vikings,’ ‘Patriots,’ or even ‘Cowboys,’” and notes that objections to them “strike many of us as political correctness run amok.” These nicknames get a free pass from Costas, though opponents of Indian mascots and team names have protested against them for years. Next, Costas lists a second tier of teams, with names that are “potentially more problematic,” but “can still be okay provided the symbols are appropriately respectful.” This leads him, implicitly, to a third tier, in mention of the Cleveland Indians, a team with a tier-two nickname that has “sometimes run into trouble” with its caricatured and hyperbolic Chief Wahoo logo. Fourth, Costas distinguishes a tier of teams, like the Stanford Indians, Dartmouth Indians, and Miami of Ohio Redskins, that acknowledged the potential for offense and changed their names, calling particular attention to Miami of Ohio. Washington is listed last and, at this point, Costas distinguishes it in its own tier, at the bottom of the list of increasingly problematic offenders. He asks viewers to “think for a moment about the term ‘Redskins,’ and how it truly differs from all the others. Ask yourself what the equivalent would be, if directed toward African-Americans, Hispanics, Asians, or members of any other ethnic group” before using this reflection and distinction to assert “When considered that way, ‘Redskins’ can’t possibly honor a heritage, or noble character trait, nor can it possibly be considered a neutral term. It’s an insult, a slur, no matter how benign the present-day intent.”

It is an original and potentially persuasive tactic. Through this series of distinctions, Costas breaks out of the stalemated, repetitive cycle of debate over Native American mascots as a whole and instead singles out the Redskins as a particular case. He is striving, here, it seems, for mutually satisfying compromise in a debate that rarely sees it. His description of team names in the first and second tier echoes perennial defense of Indian mascots, while his indictment of the lower tiers aligns more with the Indian mascot objectors’ familiar words and stance. With distinction between types of team names, Costas is seeking to affirm the arguments of both sides but also make room for compromise.

Yet we might also question the efficacy of such tactics. By excusing some teams with Indian-inspired nicknames of any offense, his words let some potential racism and insult off the hook. By equivocating and distinguishing between names and mascots, he is, in some ways, conceding parts of the “Change the Mascot” fight. Advocates of abolishing all potentially offensive nicknames might accuse Costas of throwing opponents of names like “Chiefs” or “Blackhawks” under the bus in his effort to critique the Redskins. Distinctions like these, while seeking to forward the anti-mascot cause on some fronts, stifle future efforts on others. The images, for instance, that appear on screen when Costas excuses the Braves, Chiefs, and Indians as less offensive incorporate tomahawks, arrowheads, and men saluting one another while concealing raised axes behind their backs. Costas does not call attention to the negative history surrounding such images when he uses them as he excuses the top tier teams. And, of course, any distinction between kinds of Indians or tiers of quality among Native American peoples or symbols hearkens uncomfortable associations with blood quantum laws and brown paper bag tests.

October 13 was not the first time Costas has dabbled in political or social commentary during a sportscast (see 8, for instance) and it is unlikely to be the last, but he seems to rankle viewers each time it happens. While seeking compromise, it’s likely that Costas pleased neither the most adamant anti-mascot campaigners nor the staunchest pro-mascot defenders. Then again, perhaps that was not his intention. Perhaps, in ending with the assertion that “’Redskins’ can’t possibly honor a heritage,” he intended his remarks as an open rebuttal and challenge to Dan Snyder’s letter. Perhaps he sought only to prompt discussion with the hope that progress made now would lead to other progress in the future, chipping away at offensive sporting nicknames bit-by-bit over time.

Whatever the intent, the situation remains unchanged. At the end of October, Goodell met separately with Snyder and with Oneida Nation representatives. The stalemate persisted. The Redskins name remains, as does the controversy. And while we have an interesting new perspective in the ongoing discussion, the defenses are familiar and offense, as Costas phrased it, continues be taken.