And…we’re back! Sorry for the long hiatus, but we’re excited to return with all new commentary on rhetoric and current events, starting with this post by Emily Sauter.

Replacing the incredibly popular John Stewart, new host of the Daily Show Trevor Noah has some big shoes to fill. Adjusting to the new host audiences must not only get used to a new face, but a host with a new accent and a wildly different background. Former host John Stewart is Jewish by birth and a native New Yorker, an identity that he used to great effect, whether for comedy or solidarity. Readers might remember Stewart’s emotional opening monologue after 9/11, where he said, “The view from my apartment was the World Trade Center. Now it’s gone. They attacked it. This symbol of, of American ingenuity and strength, and labor and imagination and commerce and it’s gone. But you know what the view is now? The Statue of Liberty. The view from the south of Manhattan is the Statue of Liberty. You can’t beat that.”

In that moment Stewart’s identity as an American was paramount and provided audiences with an anchor point of empathy. Trevor Noah has no such point of connection. Instead, he must use his background as a South African as a chance to build new comedic opportunities, to stand outside the American institution and comment on it. As a correspondent Noah made his debut in December of 2015 with a short segment titled “Spot the Africa.” In the segment Noah talks about life in Africa versus life in America, and in what might be a surprise to some viewers, the comparison does not work out in America’s favor. In one joke he says, “Africa’s worried about you guys. You know what African mothers tell their children? ‘Be grateful for what you have, because there are fat children starving in Mississippi.’” He then presents Stewart with a jar full of pennies and a song, “Feed America.”

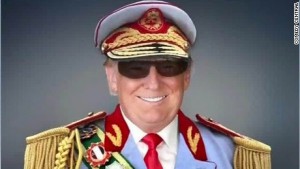

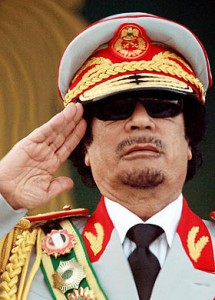

During the segment Noah switches back and forth between referring to South Africa specifically, and Africa at large. Considering American audiences have little to no knowledge about Africa or the differences between nations, the conflation is concerning. This trend continues in one of his newest segments as host of the show, where he compares Donald Trump to an “African President,” using clips of Jacob Zuma (president of South Africa), Yahya Jammeh (president of Gambia), Rob Mugabe (president of Zimbabwe), Idi Amin (former president of Uganda), and Muammar Gaddafi (former leader of Libya). Throughout the segment an image of Trump is decked out in increasingly ludicrous faux-military medals and sashes. The ensemble is then topped with a pair of black shades—the perfect African President.

The segment is funny, no doubt about it. And there are indeed some eerie rhetorical similarities between Trump and Africa’s most notorious dictators. For example, both Trump and President Zuma of South Africa claim “most” immigrants are criminals, though not all—a rhetorical choice that Noah labels “light xenophobia with just a dash of diplomacy.” The President of Gambia claims he can cure AIDS using bananas, and Trump claims vaccinations cause autism. In perhaps the most amusing comparison of the segment, Noah links Trump’s bragging about his money and his brain to Uganda’s Idi Amin, who is shown in a series of clips to be making the same claims to wealth, popularity, and intellect.

However, Noah’s attempt to use his African heritage as a prop to mock the American presidential candidate does more harm to America’s understanding of Africa than it does to Donald Trump. At best Trump looks absurd, maybe delusional; at worst he looks crazy.

Let’s look more deeply at the comparisons Noah used shall we? Muammar Gaddafi was condemned internationally for his egregious violations of human rights against his own people, suspected of ordering the bombing of Pan Am Flight 103 where almost 300 people died, and considered AIDs as a “peaceful virus.” Idi Amin’s rule was characterized by human rights abuses, political repression, ethnic persecution, extrajudicial killings, nepotism, corruption, and gross economic mismanagement. International observers and human rights groups estimate that 10,000-50,000 people were killed under his regime. Robert Mugabe has been president of Zimbabwe since 1980, and between 1982 and 1985 at least 20,000 people died in ethnic cleansing and were buried in mass graves. Yahya Jammeh has been “elected” several times under suspicious conditions, has introduced legislation that would result in beheading for any LGBTQ citizens, has had students and journalists killed, has reportedly “disappeared” or indefinitely detained those who oppose him, and has instigated a literal witch hunt that has killed hundreds. Jacob Zuma, Noah’s own president, is certainly not considered the cleanest of presidents. He has been charged with corruption, rape, and has been involved in a number of scandals.

Noah has unprecedented access to the American public and a true chance to help educate us on the many differences between African nations in general and the reality of a place like South Africa specifically. What audiences encountered during this segment was not a funny insightful joke about Trump’s more dictatorial theatrics, but the enforcement of harmful western narratives—that “Africa” is violent, dictatorial, and unable to maintain any sort of true democratic government. I admit, as someone who studies South Africa I was incredibly excited to see Noah step into the role as host of the Daily Show, hoping to see a representative of South Africa who could bring more understanding to an audience woefully lacking information on the country. If this is the caliber of comedy that I can expect from Noah though, I think I’ll take a pass on future episodes.