بسم الله الرحمن الرحيم

In the Name of Allah, The Compassionate, The Merciful

Fifteen years following the 9/11 attacks, and studies show that Islamophobia is worse than ever. One reason that remains under-examined is the manner in which we use Islamophobic rhetoric to talk about ISIS. Rather than doing anything to actually “defeat ISIS” (to quote several politicians), all this rhetoric does is normalize anti-Muslim racism.

First off, it is worth noting that Islamophobia is a confusing term. It insinuates a “phobia” or fear of Islam and, by extension, Muslims. However, reducing Islamophobia in such a simplistic manner does not address the systemic and historical roots of anti-Muslim aggression — namely that it stems from colonial discourses of white supremacy. Put simply, Muslims are technically a religious demographic; but, Islamophobic rhetoric has racialized Muslims as Brown people belonging to a pre-modern civilization that is inferior and subordinate to that of the West. This casts a wide net of who actually experiences Islamophobia: from non-Muslim Arabs, signified by the murder to Khaled Jabara by a neighbor last month, to Sikh men who adorn the turban for religious reasons. This is also why Jaideep Singh even goes so far as to argue that the term Islamo-Racism should replace our use of Islamophobia, with others preferring to use the term “anti-Muslim racism.”

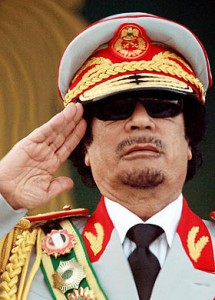

When this rhetoric of Muslims’ inferiority is used to shape our understanding of ISIS, all it does is instrumentalize ISIS to rationalize structural anti-Muslim racism. This was demonstrated well during the Republican and Democratic national conventions this summer where Muslims were portrayed either as ISIS affiliates or individuals willing to work with the state to defeat ISIS-like radicalization. In his RNC speech, for example, Donald Trump framed his ambition to “defeat the barbarians of ISIS” by strategically placing the attack in Nice, France, alongside a myriad of other examples in the U.S., including the 2001 attack on the World Trade Center and the recent Pulse nightclub shooting in Orlando, FL. In doing so, Trump spoke through a false dichotomy wherein the victims of ISIS are uniformly Western, and marks the aggression as a coherent, linear brand of “Islamic terrorism.” In proclaiming this violence as inherently and solely “Islamic,” however, his rhetoric leaves no room to address that Muslims are actually the primary victims of ISIS. July alone, for instance, witnessed one the deadliest attacks in Baghdad, Iraq since 2003 killing over 250 (predominantly Shia) people in the Karada shopping district; one of the deadliest attacks in Kabul, Afghanistan since 2001, killing over 80 Shi’i Hazara Muslim; and an attack in Istanbul, Turkey killing over 40 people.

Donald Trump speaking at the 2016 RNC

Unlike Trump’s RNC speech that promoted an “Islamic radicalization versus the progressive West” narrative, the DNC fueled a classical “good Muslim”/“bad Muslim” narrative in which the “good Muslim” was one eager to cooperate with the state to defeat radicalization. Bill Clinton stated this point blank by proclaiming, “if you’re a Muslim and you love America and freedom and you hate terror, stay here and help us win and make a future together.” Several Muslims immediately pointed out via social media the manner in which Muslim loyalty was put on trial. It may also be worth noting that neither of the candidates – Hillary Clinton or Donald Trump – even mentioned the word “Muslim,” and that the only time Trump did was in reference to the Muslim Brotherhood. This means that Muslims were invisible in both conventions, unless and until terrorism and/or militarism was brought to the forefront.

What the language in the speeches demonstrates is that anti-Muslim racism in today’s ISIS hysteria-ridden/post-9/11 context paints Muslims as if they have been infected by this thing called “Islam.” If it is not surveilled and monitored properly, this will turn into the virus we now call “radicalization”; but with proper care, this radicalization will lie dormant. This was particularly clear in the fear that Trump spurred through his application of “radical Islam,” and in Bill Clinton’s plea with Muslims to stay in the U.S. so long as they can fulfill their “responsibility” to fight terrorism (insinuating that Muslims would have insight into terrorism by virtue of being Muslim).

What’s more, the entity responsible for controlling the “radicalization” outbreak, is the State itself. That is, the federal government has taken it upon itself to cure the nation of this illness by enlisting the help of the U.S. public, and especially Muslims and Arabs themselves, to participate in the surveillance process. Anti-Muslim rhetoric, then, reinforces the need for control and surveillance through the fear of radicalization.

Muslims demand equal rights in a 2013 U.S. protest.

The language of fear, responsibility, and control that was extolled throughout the convention speeches has material consequences that structure anti-Muslim racism, particularly through state and federal policies. This includes (but is not limited to):

- Support for surveillance programs such as the “Shared Responsibility Committees” which ask counselors, teachers, and community leaders to help the state identify individuals who have been potentially “radicalized.” These rely heavily on the use of “suspicious activity reporting,” which, some claim, has questionable and unsuccessful methods.

- Rationalized forms of racial profiling, particularly through the use of community informants. This, arguably, encourages Muslims and Arabs to engage in the State’s work of criminalizing their own communities. Since the informants are community members, this allows the federal government to evade the accusation of direct racial profiling.

- The prevalence of anti-Shari’a legislation in nine states, even though Shari’a was never practiced in U.S. court systems.

- The stigmatization of refugees seeking asylum simply on the basis of ethnic and faith-background, as indicated by attempts by state governors to deny refugees asylum — even though they do not hold that power.

- The emboldening of policies such as the Countering Violent Extremism Act, which may make innocuous acts of Muslim worship appear suspect, thereby further criminalizing Muslims for merely observing their faith. The CVE website “Don’t be a Puppet” reflects the manner in which not engaging in the acts of surveillance renders you “a puppet” that may, one day, be responsible for the presence of radicalization within our country.

As a necessary point of clarification, I am not trying to argue that nothing should be done or that “extremism” doesn’t exist – as a Shia Muslim woman myself, I belong to one of the most targeted groups of ISIS; however, the “countering extremism” measures here promote structural anti-Muslim racism by criminalizing Muslim communities, and renders Muslim victims of both ISIS as well as structural anti-Muslim racism, completely invisible. This is enhanced through the rhetoric surrounding radicalization, responsibility, and control.