This post was co-authored by Kevin Musgrave (UW-Madison, Communication Arts) and Jeff Tischauser (UW-Madison, Journalism and Mass Communication).

The brash new wing of the conservative movement, the so-called “Alt-Right,” has drawn public attention and ire, with Democratic Presidential nominee Hillary Clinton condemning them in a recent campaign speech in Reno, Nevada. Despite this recent publicity, questions abound. Who exactly are the “Alt-Right?” How do they differ from other conservative groups and what are the defining characteristics of their rhetoric?

Clinton condemns the “Alt-Right” in Reno

Though many prominent media outlets including the New York Times, Salon, the Daily Beast, as well as media watchdog groups FAIR and Media Matters have published pieces on the group, a solid conceptualization of the “Alt-Right” remains elusive. Emerging from these pieces, however, is a list of common characteristics that may allow us to articulate the defining communicative and rhetorical norms and strategies of the “Alt-Right.”

The “Alt-Right” is often defined with and against the development of the New Right, a nebulous conservative movement represented by the rise of Barry Goldwater and Ronald Reagan. Blending fiscal and social conservatism with a strong military presence and foreign policy, the New Right offered a means of fusing what rhetorical scholar Michael Lee calls the conflicting dialects of traditionalism and libertarianism that constitute the political language of conservatism in the United States.

Yet, if Reagan has become synonymous with the fusionist message of the New Right, the “Alt-Right” has emerged within a conservative vacuum that has seen the Republican Party, post-George W. Bush, struggle to create a message capable of unifying traditionalists and libertarians alike. Indeed, what the “Alt-Right” appears to be doing in its rhetoric is actively delinking these two dialects, re-articulating an extremist traditionalist message, and separating the language of conservatism from the Republican Party.

Manifesting primarily in online forums such as 4Chan, Reddit, and RadixJournal, the “Alt-Right” consists mainly of 18-35 year-old white males who are, as their leader Milos Yiannopoulos claims, “young, creative and eager to commit secular heresies,” through the creation and circulation of openly racist, sexist, and nationalistic memes.

The usage of these memes is a way of signaling belonging to the group by demonstrating a fluency in the “Alt-Right” vernacular. The memes are marked by the conspiratorial style of a white genocide narrative, an ironic deployment of racial tropes, protectionist rhetorics of white tribalism, and a European Anglo identity politics premised on racist pseudo-science.

In advancing a return to tribal politics, the “Alt-Right,” as Jack Hunter of the Daily Beast argues, defines itself against the radical individualism of the libertarian dialect as articulated by conservative firebrands such as Goldwater. Denouncing individualism in favor of a radical traditionalism that calls for a return to communal, authoritarian, and hierarchical politics premised on racial difference, the “Alt-Right” abandons the religious metaphysics of Russell Kirk, Richard Weaver, and other traditionalists in favor of a racial science that justifies a disdain for egalitarianism and democracy.

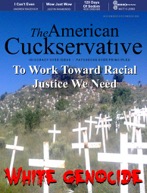

One prime example of how those in the “Alt-Right” use memes to circulate these messages is the common term used by its members: “cuck.” This term rhetorically defines the “Alt-Right” as opposed to establishment Republicans–cuckservatives–maligned by the “Alt-Right” as neocons and liberal Republicans pushing an internationalist agenda that threatens the white race.

In the satirical depiction of the American Conservative magazine below, internet users have fashioned the publication as a cuckservative mouthpiece, promulgating the death of the white race in efforts to achieve social justice. Advancing a conspiratorial narrative that views immigration, inclusion, assimilation, and diversity as an affront to white masculinity and racial purity, the cuckservative is one who has emasculated himself, become a traitor to his race, and permitted the affordance of a white minority population and colored body politic through liberal policies that advocate for pluralism and equality.

Engaging in racist pseudo-science to support claims of white supremacy, the “Alt-Right” not only biologizes racial difference but also uses hereditary and cognitive science to argue against egalitarianism. In this way, the values of the Enlightenment philosophy of classical liberalism, heralded by the libertarian right, become anathema to core “Alt-Right” tenets of communal, tribal belonging, racial hierarchy, and authoritarianism. In redefining conservatism this way, the “Alt-Right” is imagining conservatism as an Anglo European identity politics and mainstreaming core tenets of white, authoritarian nationalism in popular discourse.

Enter Pepe the frog, a character previously associated with #gamergate, anti-semitic attacks on journalists and activists, and the male rights movement. Pepe plays to members of the white in-group who understand the joke for what it really is, a call to action. In this sense, Pepe is the wink after the racist joke. The rhetorical power of Pepe, like the racist joke, is that it lets its purveyors escape with plausible deniability. The ironic detachment that emerges in Pepe’s history helps to conflate intention with effect, allowing users to distance themselves from its often racist connotations. Rendering Pepe in Hammerskin Nation-like attire, covered in blood, carrying guns used by Nazi SS Stormtroopers, is not racist, or disrespectful, rather it’s an irreverent way to shock and disrupt PC culture. Sharing Pepe memes allows members of the “Alt-Right” to espouse its “fuck your feelings politics,” distancing themselves from liberals and mainstream conservatives through vitriolic rhetoric.

When the Trump campaign tweeted an image of himself as Pepe in October 2015, to @BrietbartNews and others, with the message, “You Can’t Stump the Trump,” he rhetorically positioned himself as the Presidential candidate of the “Alt-Right.” As a candidate whose views on American exceptionalism, immigration, and anti-PC culture resonate with the message of the “Alt-Right,” Trump stands as a figure capable of making white nationalist ideas a political reality.

Trump thus represents the power to create a sovereign nation state that protects white men from perceived economic and cultural threats. However, Trump stands more as a vehicle for the “Alt-Right” ideology than its driver. Even as Trump’s appeal appears to be diminishing with conservatives, his core “Alt-Right” constituency, aided by an array of “Alt-Right” media outlets and its dedicated meme warriors who troll Reddit and 4Chan, the “Alt-Right” as a political force is not going away any time soon.